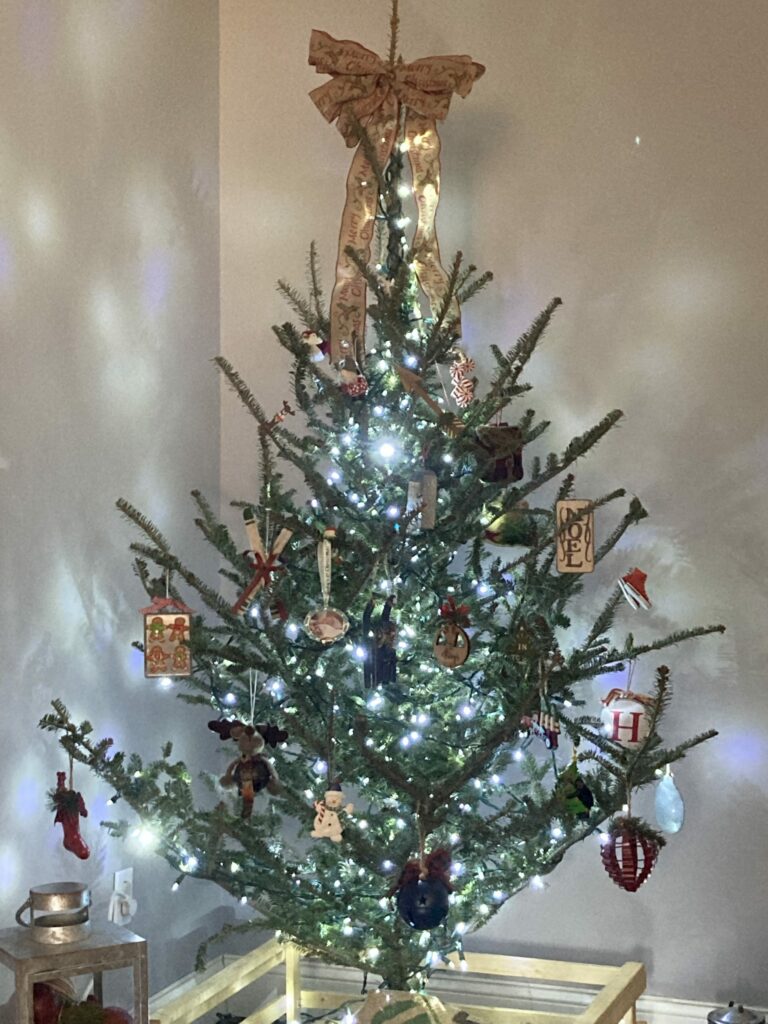

Pictured: A Christmas tree in its natural environment; this particular specimen provides habitat for over 23 species of ornaments, which would otherwise be confined to boxes in a dark basement.

By: Mark Halpin, Forestry Manager

What could possibly be the tree of the week this week, but the Christmas tree? Growing to heights that vary from 12 inches to 120 feet, the Christmas tree prefers an extremely moist environment because it has no root system, and needs to have water introduced directly into its trunk. This is typically done by submerging its base into a trough of water. Stability is an issue; with no structural roots, these trees are susceptible to collapse, with dogs, children and drunken relatives being common agents of destruction. Water should be replenished frequently, as a dried-out Christmas tree not only loses its beauty and fragrance rather quickly, it is also liable to become a serious fire hazard. This is compounded by the presence of lights or, if you are a traditionalist and thrill-seeker, the presence of actual lit candles that people in the past were crazy enough to place on their trees. (The benefits of things like ginger ale or “Christmas tree food” added to the water have eluded science as of this date).

The Christmas tree is no particular species; any evergreen will do, preferably a needled conifer. The more fragrant, the better – Fraser fir, Scots pine, and noble fir are popular species in North America. There have been efforts to assign an ancient pagan origin to the Christmas tree, but all historical sources seem to indicate this tradition originated in 16th century Europe among Lutherans. Of course Christmas itself is an amalgamation; a Christian celebration grafted onto various pagan Solstice and harvest traditions (yule logs, mistletoe, caroling or “wassailing” as it was originally known, etc.) and veneration or even worship of trees was a common feature of ancient traditions everywhere that trees grow (showing that humans the world over have good taste). Evergreens in particular have long served as symbols of immortality as they seem to defy the seasonal “death” that the rest of the botanical world succumbs to in winter. So maybe there is some ancient pagan influence, buried deep under the surface…

I’ve always felt part of this desire to assign ancient provenance to the Christmas tree tradition came from people who want to participate in it, but aren’t religious. The Christmas tree, however, was being adopted into European Jewish homes as early as the mid-1800’s, when it was seen as a symbol of winter festivities and life, with no particular religious allegiance. The boughs of a conifer, standing in green defiance of the grey world surrounding them, are such an archetypal symbol that they speak to something in all of us. If it speaks to you, bring one into your home, for whatever reason you wish. In a season in which love for our fellow humans, and goodwill towards all are the values we are meant to be celebrating, anything that can bring us closer together (up to six feet, that is) is to be applauded.

Whether or not real Christmas trees are better for the environment than artificial ones is hotly debated, and much depends on how the trees are produced. A well-managed tree farm – one that minimizes chemical use and unneeded irrigation – is without a doubt beneficial for the environment. And recycled Christmas trees can be used to make mulch, as fish habitat by sinking them in lakes, even for erosion control. (They make terrifyingly festive bonfires, to warm the blood on a frigid January night. Stand well clear when you first light one). I myself am not a practicing member of any faith, but every time I see any tree I am thankful to be alive, and to be surrounded by such beauty. To me the Christmas tree is a celebration of life, and so I joyfully participate in this tradition.